The year 1974 looked bleak for the auto industry. The oil embargo that had quadrupled gas prices overnight was a few months old. Federal smog emissions regulations had added limits on oxides of nitrogen to an industry that was largely clueless about solutions. This led to monstrosities like an 8.2-liter Cadillac V-8 that could muster no more than 190 horsepower.

Europe wasn’t as severely hamstrung by emissions regulations, but the price of fuel exploded there too. In West Germany, the government responded with bans on Sunday driving and 62-mph speed limits—not only on the autobahn but also on racetracks. These were short lived, but the atmosphere did not favor high-powered cars. BMW, which, through the instigation of sales vice president Bob Lutz, had introduced the 2002 Turbo in 1973, withdrew it in less than two years’ time. Lutz believes the unfortunate timing accelerated his departure from the Bavarian firm.

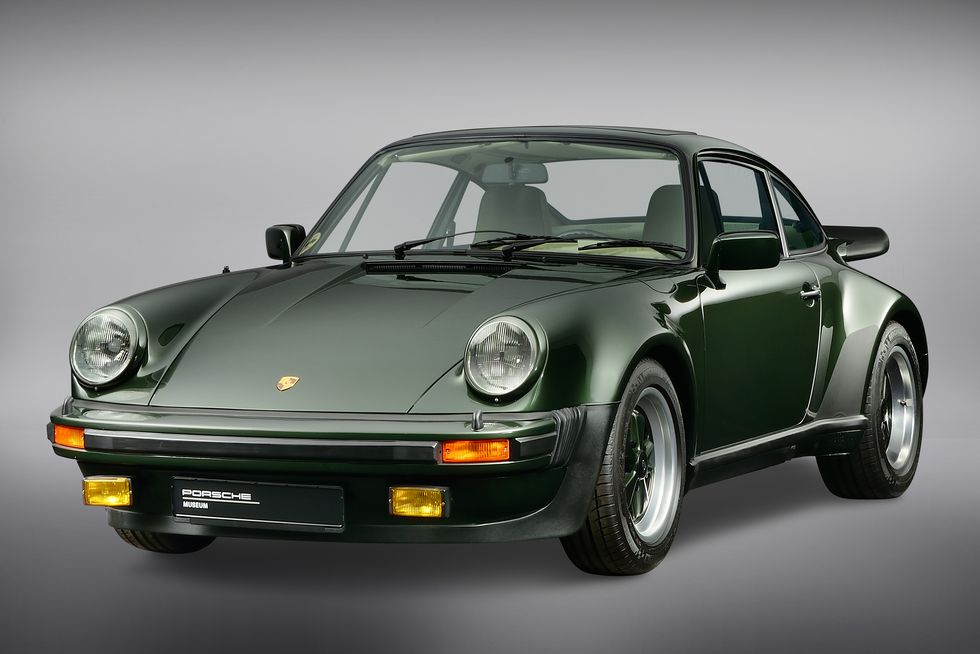

Porsche, however, took a different path and introduced its Turbo at the Paris auto show in October 1974. The company’s CEO, Ernst Fuhrmann, kick-started the development of a turbocharged 911 based on the success of the 917/10 racer that had won the 1972 Can-Am championship.

It was a G-model 911—the first of the short-hood, square-bumper cars—but with wildly swollen fenders to accommodate the wide (by 1970s standards) rubber needed to cope with the engine’s power. That engine was a 3.0-liter version of the iconic air-cooled flat-six, fitted with a single KKK turbocharger, pumping 11.6 psi of boost—sans intercooler—into cylinders operating at a lowly compression ratio of 6.5:1. Fuel metering was provided by a Bosch K-Jetronic system, a simple constant-flow electromechanical fuel-injection system.

Though primitive by modern standards, the hardware achieved 249 horsepower at 5500 rpm and 243 lb-ft of torque at 4000 rpm. This was at a time when the 911 Carrera RS—the homologation special that introduced the ducktail spoiler—could muster only 200 horsepower at 6300 rpm and 175 lb-ft at 5100 rpm.

When the Turbo arrived in the U.S. in 1976, emissions controls had sapped the output, dropping power to 234 horses. But that was still sufficient to rocket the 2825-pound Turbo to 60 mph in 4.9 seconds, through the quarter-mile in 13.5 seconds at 103 mph, and on to a top speed of 156. At the time, the fastest 911 in the U.S., the 157-hp Carrera, needed 6.2 seconds to hit 60 mph and 14.9 seconds to cover the quarter. For some sports-car context, the 1977 Corvette weighed some 700 pounds more, was powered by a neutered 5.7-liter V-8 with 180 horsepower, and rumbled through the quarter in 16.1 seconds before running out of thrust at 123 mph.

Porsche positioned the Turbo as not only its fastest model but also its most luxurious. It came standard with most Porsche options and even included items like an automatic temperature-control system, a big advance when the quantity and temperature of your heat came from an air-cooled engine with wildly varying thermal output. The Turbo Carrera’s base price of $25,975 reflected this flagship status.

Despite the big rear tires, which provided sufficient traction to properly launch the Turbo, the handling left a bit to be desired. All 911s back then suffered from what is politely called trailing-throttle oversteer. This means that when you are cornering hard and lift off—or even ease off—the throttle, the rear end of the car loses some traction and the tail tends to drift out. This characteristic seems exaggerated in the Turbo, perhaps because that much power put a bigger whammy on the rear suspension. It seems that quite a few examples departed pavements tailfirst, and the car acquired the nickname “the Widow Maker.”

Knowing all of this left me with mixed feelings when the Porsche Museum’s Kai Roos asked me if I wanted to take a 1977 Turbo for a brief drive. And by the way, this beautiful Oak Green Metallic car with custom buffalo hides, green tartan cloth, and a mere 10,800 miles showing on its odometer was also Ferry Porsche’s company car when new. It was pouring rain during the late-afternoon rush hour on Stuttgart’s suburban roads surrounding the museum. Of course I took it out.

Despite the Turbo being the top-of-the-line and plushest Porsche in its day, it carried hardly any creature comforts. No power steering, basic seats with no power adjustment or lumbar support, and, of course, no screens. The transmission is a basic four-speed manual—having lost a ratio when the gears were widened to cope with the Turbo’s increased output—with the classic floor-pivoting clutch pedal. First gear is a little tall, but the Turbo is easy to get going, even though the engine is completely off boost at low revs. The shifter throws are very long by modern standards, and the lever is a bit far forward, as is the steering wheel. But the mechanism works smoothly and easily, with excellent gear spacing, despite having only four.

The engine is definitely strong, and though turbo lag is considerable at 2000 rpm, it disappears progressively at higher revs. Toe into it at four grand, and the engine responds immediately with a strong, but not sudden, push in the back. Despite its age, this Turbo was healthy and even with the traffic and the rain. On the autobahn, fourth provided decent throttle response without feeling too busy. In town, second worked well over a broad speed range.

With the car weighing as little as it did—a claimed 2635 pounds—I didn’t miss power assistance on the steering, which was precise and accurate. And the brakes, which did have a vacuum booster, felt firm through the pedal but easy to modulate. This Turbo felt more mechanical than any modern car, with more engine noise and less road noise. And unlike in modern cars with their higher beltlines, I sat high and upright in the Turbo, with great visibility in every direction. It was great to drive.

I couldn’t help comparing the Turbo to my 2017 911 Carrera, which also happens to have a turbocharged 3.0-liter flat-six. Even though my car is the lowliest 911 of the 991.2 generation, it has about 40 percent more power and torque than the ’77 Turbo, thanks to intercooling, direct injection, water cooling, and the miracle of modern computerized engine management. Though it weighs about 400 pounds more than the U.S. Turbo, it lunges to 60 mph in 4.0 seconds, gets through the quarter in 12.4 seconds, and tops out a little over 180.